France's 'Tres Petite Voiture' TPV (later, 2CV). The Colossal Risks That Saved Citroën's 'Very Little Car'

“Nazis, the Resistance, & Daring, Oh My!

“Ce ci n’est pas un voiture….c’est un art de vivre” (“This is not a car…it’s a way of life”)

To truly grasp the essence of France—its heart, its spirit—it helps to understand its rich history, with tales of struggle and moments that have shaped the nation. Among these is Citroën’s Très Petite Voiture (TPV), the prototype that would give birth to the iconic 2CV.

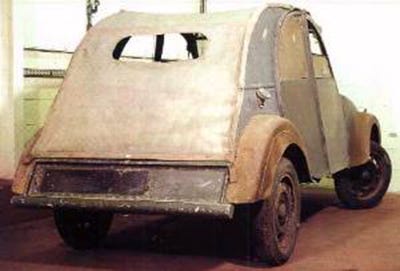

Early TPV, built but, alas, not shown. Early prototypes were hidden during WWII.

What’s not to love? One light, one wiper, no outside handle. Designed to run on gas rag vapors and be cheaper than Borscht to run….! Image here

The journey of this "Very Little Car" is a tale of white-knuckle-risks, bold innovation, and grit with a capital Grrrr. It was designed to improve the lives of everyday French people, but nearly didn’t make it. But with pluck, a dash of risks, and a desire to create something for the masses, Citroën, led by one PJ Boulanger, pulled off a miracle.

The story behind the TPV goes far beyond the realm of car enthusiasts. (Attention, streaming execs—your next big project?) It’s a tale of boldness and calm, a perfect blend of daring and legendary resolve under pressure. (Oui, it’s pure legend.)

One-eyed minimalism

Till we get script approval let's start with Pierre-Jules (PJ) Boulanger, the hard-core Frenchman whose pluck and in-your-face Nazi-defying grit, saved the world's first true working-person's car. (How’s Vincent Cassel as Boulanger and Christoph Waltz as the evil Ferdinand Porsche?). But first, the backstory….

Way Back In The Day

A Horse, A Cart and the Birth of a Legend

Pierre-Jules Boulanger became general manager of Citroën after Pierre Michelin acquired the company in 1934. Once in the corporate saddle he forged ahead with what would eventually become the 2CV*. Boulanger was keen on giving Frances' rural-based Jean-Luc’s and Amelie’s that sorely needed affordable, practical car!

* ‘CV’ for ‘Chevaux Vapeur’, “which translates to ‘horsepower’ in English. This term, commonly used in Europe, is a measurement used to describe the power output of an engine. In the case of Citroën 2CV, the ‘2’ represents two taxable horsepower, while the ‘CV’ denotes the French fiscal horsepower rating system”. Source

A Slow Horse to Nowhere

Legend says that on some long-ago rainy day while stuck in his car behind a farmer whose horse was doing molasses speed on a narrow lane, Boulanger (VP & head of Engineering & Design), had the epiphany: Create an affordable, dependable, simple car for France's mostly rural population which needed dependable, low-budget transport. At the time many people still relied on horses to transport goods and get around, plus had to commute long distances. Surely, he must have thought, we can offer folks a better way. (He became president in 1937).

You winking at me, sexy? - Restored Citroën TPV with a single headlight

Citroën management was also aware of the situation: “Members of Citroën’s top brass noticed a growing problem in the middle of the 1930s: Most of the company’s blue-collar employees couldn’t afford to buy a new car. Some borrowed money from friends or relatives and spent years paying it back, while others settled for a used car that often cost a small fortune to keep running” Full account here. Footnote:

Boulanger’s novel idea was to design a car based on the needs of working farmers and families, that is, first establish what those criteria are, and then design a car to match them. Probably similar to today’s "User-Centered Design" (UCD) or "Human-Centered Design" (HCD), which focuses on the needs, behaviors, and preferences of the end user first. Pretty visionary for back then.

DESIGN HIGHLIGHTS

Based on Boulanger’s team insights the TPV had legendary design criteria: Including:

“... create a car that can carry four people and 50 kg of potatoes at 60km/h, while consuming just 3 litres of fuel per 100km... (80 miles per US gallon or 95 per British Imperial gallon)….and don't worry about how it looks...”

“The TPV is like a bicycle with four seats. It needs to protect its occupants from rain and from dust on a dirt road, and it needs to reach 60 or 65 km/h in a straight line on a flat road,”

“The auto had to be able to cross a plowed field with a box of eggs on the backseat, without breaking any”!

EASY FOR WOMEN & LEARNERS TO START & DRIVE

The TPVs next-level revolutionary specs required it to be easy for women to start and drive, and be able to run for 30,000 miles (50,000 kilometers) before replacing any mechanical parts. Further it had to run on the smell of a gas rag, and be cheaper than borscht to fix, (I paraphrased those last two). The car was designed to need (mostly) but one screw type. I think there were three types in all.

“The TPV needed to be easy to repair by someone who knew absolutely nothing about cars. Achieving this required reducing the number of moving parts to the bare minimum and ensuring everything was easily accessible”. Source:

“The initial seats were hammocks hung from the roof by wires”, and the roof itself was literally a 'rag-top' - cloth that got rolled back. (Probably to reduce weight and costs). Its first early (prototype) engine (at 500cc) was yanked from a BMW motorcycle.

My favorite spec was a unwritten preference for hiring night-school engineering graduates as it was thought they had a 'better grasp of reality' than their day-time, grandes écoles colleagues.

And we just have to add: Getting in the car meant first sticking one's hand through the window to grab the interior door-handle and opening the door from the inside

As French law at the time required only one windshield wiper, that’s exactly what the TPV got—one wiper (whose speed was linked to the driving speed). This 'one only’ law also applied to headlight(s) — as only one required, only one was used. This changed after oncoming drivers complained it looked like a motorcycle.

BRIEF START: Initial work on prototypes, dubbed TPV (tres petite voiture), began in a secluded locale west of Paris, away from prying eyes. The Citroën design crew included André Lefebvre (engineer) & Italian stylist Flaminio Bertoni.

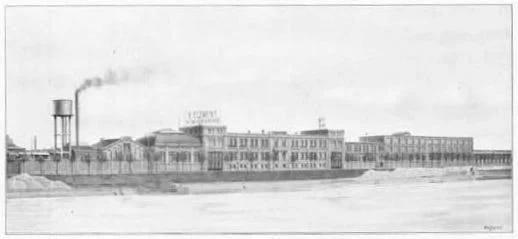

After a staggering 47 prototypes were produced and evaluated, Citroën chose a design and began producing some 250 ‘pre-series’ cars at its Levallois factory. Plans called for launching the radical car at the upcoming October 1939 Paris Car Salon. (Research says Citroën sold some 100 street-legal cars before the war (not prototypes). Read the fab source here.

But there would be no launch. History, with a capital 'H' barged in, in the guise of WWII and invading Germans, with a capital Grammerbold* 'G'. On September 3rd, 1939 France had declared war on Germany following its invasion of Poland.

To protect the company and the its prized prototype, Citroën was going to have to adapt and be clever about it.

Old form of German handwriting from the 16th century through to the 20th.

WWII & the Germans... Again! The Fate of TPV Prototypes

By July of 1940, and after the lull of the so-called Phony War, the Germans were in Paris (and in control of northern France). If he was going to protect the TPV as well as safeguarding Citroen generally, Boulanger was going to have to walk a tightrope between likely Wehrmacht demand and preventing the wholesale theft of valuable company assets.

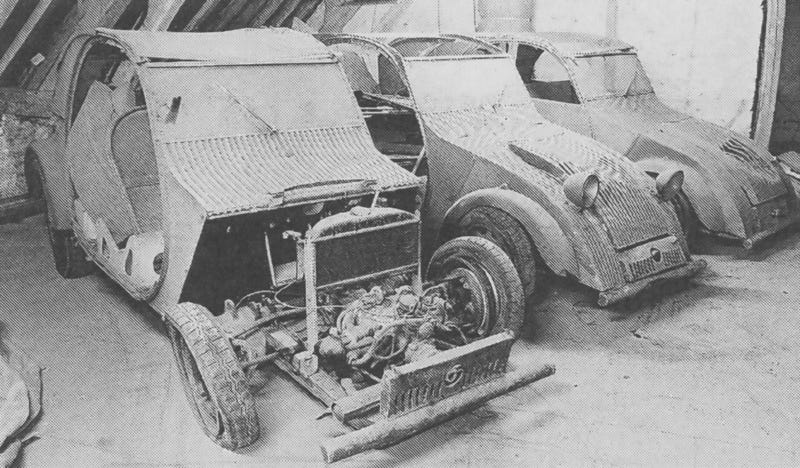

Fearing the likely repurposing of Citroen factories to serve Wermacht war production, plus the danger of the TPV falling into German paws, Citroen ordered all 250 prototypes destroyed. But, thanks to some gutsy employees, at least three prototypes were surreptitiously shipped south to Citroën’s test track at La Ferté-Vidame, with one boldly hidden in Citroën's own rue d’Opéra offices. Another was camouflaged as an ordinary truck to throw off any curious German eyes—which may have worked too well: It was sold in the 1940’s by mistake. (Now owned privately, near Lyon). The prototypes lay hidden for more than five decades. (For recent info on German skullduggery vis-à-vis attempts to obtain the the prototype click here.)

Then, in the mid-'90s, three prototypes were discovered in La Ferté-Vidame! The cars were so well hidden that it took a herculean effort to retrieve them. Given France's wartime experiences and the sheer number of barns and out-of-the-way locales, it’s hard to imagine there aren’t more cars still awaiting discovery!

What Lies Within:

Beneath years of dust and silence, their true worth was never diminished nor lost—only hidden, waiting a time to share their priceless story.

A little gas, some oil, air in the tires and we’re good to go.

Three TPV’s: One has one headlight, one has two, and one has none!

Back to Boulanger and his Citroën Team

Boulanger was clearly forged from some very rare 'right' stuff – an hombre with a titanium backbone who wasn’t about to let a war deprive him of a his dream. An ex-WWI French Air Force captain and twice-decorated* hero, the only thing Boulanger probably loathed more than Nazis were Nazis in his country, in his factory, giving him orders about his car. And one of the first, which he defied, was a ban on any 2CV design work – a restriction cleverly circumvented by the 2CV team, which continued to meet in secret. *(Military Cross and the Legion of Honour).

Sang-Froid à la Française. Over four long years of occupation, Boulanger and his team did everything possible (without being shot for sabotage) to slow Citroën’s production for the Wehrmacht. Of the many ingenious sabotage tactics they employed, two stand out:

1 The Genius Oil-Stick Con: During T-45 truck production, a heavy-duty truck favoured by the Wehrmacht, that little notch on the oil dipstick which indicated "full" was lowered, moved down, to let drivers think there was sufficient oil in the engine.

The beauty of this move was that when trucks later seized up or went Kaput at inconvenient, far-from-garage points, the cause was chalked up to wartime conditions--rugged terrain, heavy use, etc, and not sabotage.

Second was the likelihood that, ever disillusioned with the trucks reliability and maintenance issues, the Germans would be less keen to spirit them to Germany. Lastly, the dip-stick was an easy post-war fix. Genius.

2 The Train Shuffle: When the Nazis tried spiriting away Citroën's press tools, Boulanger tapped the French Resistance to misdirect trains carrying stolen materials. Instead of reaching the Fatherland, Citroën's precious freight was scattered across France and parts of Europe. Not all the wagons may have made it back to Citroën, but hey... clever. (Other tales suggest key production materials were buried, stashed or otherwise disappeared)

Boulanger, ever the defiant hero, apparently refused to meet with Ferdinand Porsche (or any German officials) except through notes or intermediaries. When Porsche requested the 2CV plans, and tried sweetening the deal by offering Boulanger a peek at a so-called ‘peoples car*’, Boulanger’s response was typically French: “Non!” *See below for real origins of the ‘people’s car.

Later that Century: Ready for the 2CV Close-Up

A decade after its initial planned unveiling the 2CV* finally got her debut at the Paris Motor Show in 1948. The car was a smash, its debut sparked an overwhelming surge of orders, capturing the attention and demand of visitors. The 2CV’s popularity was so overwhelming Citroën had to create a wait-list. What began as a three-year wait quickly stretched to five, fueling a market where used 2CVs often sold for more than new ones—simply because they were available sooner! Despite being ridiculed as the Ugly Duckling; Tin Snail; Old Tin Can or Le Canard, the car was phenomenally popular.

Selling like Hotcakes

Le Deudeuche (French nickname for the 2CV)

Thanks to Boulanger, his team, and some nervy ploys, the Tres Petite Voiture/2CV not only survived WWII to become a French—and arguably global—engineering icon but eventually attracted a generation embracing environmentalism and sustainable living.

The launch of the Citroën 2CV in 1948 was beyond a showcasing of France’s technological ingenuity; it was a bold reaffirmation of the country’s resilience and swift recovery in the wake of war and foreign occupation.

In short, it was a visionary, affordable, and practical car—perfectly in tune with the needs of the post-war generation and destined to be embraced by the one that followed. Simply put, it was a symbol of the French spirit.

Not so faint 2CV praise

"You will remember from reading your Suetonius that the proudest boast of the Roman Emperor Augustus was that he had found the city brick and left it marble. In the same vein, Citroën may claim to have found the automobile a motorised cart and made of it a magic carpet." LJK Setright

End of the Road

Before rolling into the annals of automotive history, nearly 9 million 2CVs (including variations) were produced. AUTOCAR magazine praised it as “the most original design since the Model T Ford.” Another journal declared it “the most intelligent application of minimalism ever to succeed as a car” —L. J. K. Setright.

The final French 2CV rolled off the assembly line in 1988, with the last one produced in Portugal in 1990.

Gone, But The Legacy Lives On

In the short Canadian National Film Board feature The Last Key, about a Parisian who sells everything but his Citroën when relocating to Vancouver, one of the many passionate Citroën owners interviewed sums up the visionary spirit and legacy of war-time Citroën: “we are never going to have that shock factor again, where someone goes out on a limb and creates something that is so completely different, that they are willing to take a chance that people are going to embrace it…”

Somewhere, PJ Boulanger is smiling…

France wasn’t alone in embracing Citroën’s values and ethos. More than 35 years after production ended, a thriving network of communities has sprung up around the globe—from Paris to Vancouver, and beyond. These enthusiasts share a deep passion for the history, style, and timeless appeal of the 2CV and other Citroën models.

Who Really Invented the ‘People’s Car’? Two Early Designs - Tatra & Barenyi

Tatra’s Victory Lap: The Czechoslovakian People's Car: That famed German "people's car?"—For starters, it seems the German Volkswagen was also actually based on the Czechoslovakian Tatra:

“Tatra launched a lawsuit against Volkswagen for patent infringement, but this was stopped when Germany invaded Czechoslovakia. At the same time, Tatra was forced to stop producing the T97. After World War II, in 1965, Volkswagen paid the Ringhoffer family 1,000,000DM in an out of court settlement.[14]” Gotta wonder what that’s worth today.

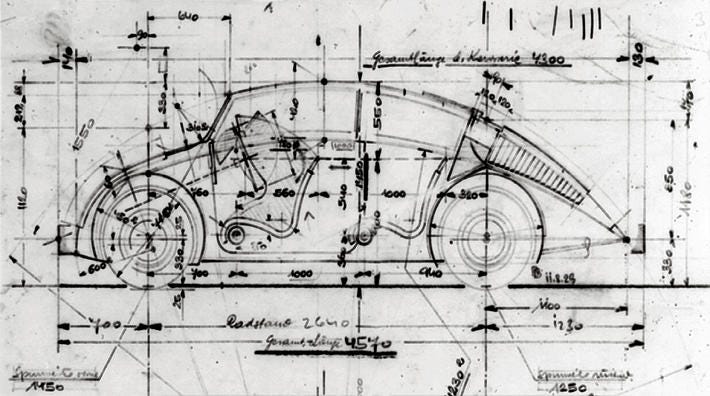

Meanwhile, A Century Earlier: The Barenyi 1925 Design. Look Familiar? And then there’s the designs of the visionary Bela Barenyi. “Tatra and Volkswagen's body design were preceded by similar designs of Hungarian automotive engineer Bela Barenyi, whose sketches resembling the Volkswagen Beetle date back to the 1925.[15]”

Barenyi has been called the most innovative car designer no one knows about.

Barenyi people’s car design some 100 years ago.

Thanks for reading. Please subscribe and pass along! Have an idea for me to investigate? You know what to do!

Thanks even more if you forward to someone. If you forgot, here ya go

2CV / Citroën Info?

Too many Citroën clubs to list, so maybe start with the Amicale Citroën Internationale (ACI) - Find them here.

UK Channel 4 documentary “The Tin Snail”, 1986

For thrilling Citroën photography : Citroënët …You must visit! https://www.citroenet.org.uk/prototypes/2cv/2cv-prototypes-3.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Canadian National Film Board’s The Last Key (2017) : Julien Capraro’s 23 superlative minute doc will leave your soul smiling, be you a car aficionado or not… Watch here:

French Language: YouTube video on Le Deudeuche, the 2CV over a few decades, a bit bizarre now.

Thanks so much for reading, and or sharing with anyone who loves great story!

Upcoming tales on 60secondparis

One of the planets’ most prolific and imaginative film directors you probably never heard of. She is…..amazing!